Lutheranism and the Ministerium of Pennsylvania: Its Beginnings to the Late 1700s

When I started this position at the Lutheran Archives, I really did not have a lot of background knowledge in Lutheranism as a religion, or the history of it nor the Ministerium of Pennsylvania as an institution. All I knew was a very minimal outline of the formation of Lutheranism in America due to my interactions with Historic Trappe and the Muhlenberg family. I figured a lot of you might be the same, though probably with different connections to Lutheranism, or might just have a general interest in American history and therefore would be interested in learning more.

Beginnings of Lutheranism as a Religion

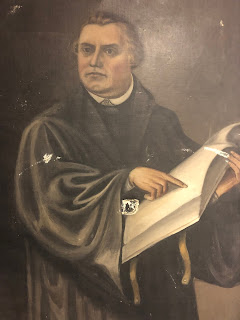

|

| Martin Luther, 1483-1546 Painted by Frans Gustaf Axelsson Morén Held by LACP |

Start of Lutheranism in Colonial America

Lutheranism had a hard time taking hold in America and in the western hemisphere in general. Early attempts to form Lutheran settlements were made in Venezuela (1528 by the Welser family; it collapsed and no presence of Lutheranism remained), in Canada (1619 by Jens Munk and chaplain Remus Jensen; most of the settlers died), and in British Guiana, or present-day Guyana (1743; this was the most successful of the three, but had issues in securing pastors). Finally, a permanent Lutheran settlement was established in the West Indies in the late 1600s.

In the 1600s, Swedish and Dutch settlements, which most likely contained some Lutherans, were formed around the Hudson, but the colony, and Lutheranism, had a rocky start. Lutherans in the area faced hardships as it was not viewed as a highly esteemed religion in the colonies; similar to Jews, Baptists, and Quakers, Lutherans weren’t allowed to publicly and freely practice their religion. Eventually, though, freedom of religion became more tolerated, allowing for the Lutheran population to not only practice their beliefs, but also to send for a Lutheran pastor; this provided further hardship, as it took a number of years before one was secured. After this and into the eighteenth century, more and more Lutherans emigrated to the New World from Europe, each creating their own small Lutheran communities. Because these immigrants had come from various countries (the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and even Poland), they each already had their own approaches to practicing Lutheranism. Adding on top of that vastly different small communities throughout America that then honed in on their own preferences for practice, Lutheranism lacked a unified identity in its structure. This continued on for a number of years, where the presence of Lutheranism, the creation of more and more churches, and the need for more pastors grew immensely.

|

| A Map of the Lutheran Church in the Time of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg Printed by MOP for the 1942 Bicentennial Anniversary of HMM in America |

At the beginning of colonization of the New World, a lot of Lutheran immigrants were Swedes and Finns. However, during the late seventeenth and, especially, eighteenth centuries Lutheran immigrants were mostly coming from Germany, settling first in areas like New York and North Carolina, but then also eventually to Pennsylvania. Unlike previous Lutheran colonists who received aid and direction from their native countries, these German Lutherans did not have any governmental or church support in their journey to and settlement of America. In fact, because conditions in Germany were quite poor due to war, famine, sickness, etc., a lot of the German Lutheran immigrants travelled to America as indentured servants, where they would be required to work off the cost of their journey for a set number of years before they could live ‘free’.

By the mid-1700s, a lot of these formerly indentured German Lutheran servants were able to buy land, and most of them decided to do so throughout central and eastern Pennsylvania. This led to vastly spread out Lutheran congregations that required their own churches, ecclesiastical literature, and pastors, all of which were very much lacking during this time. Especially acquiring officially ordained pastors was difficult because they could only come directly from Europe, a process which was very slow moving if any pastors were sent at all. This led to congregations being led either by clergymen from other Reformed sects, or else by ‘fake’ (i.e. not officially ordained) Lutheran pastors. Eventually, the few congregations that were led by true Lutheran pastors grew frustrated with the situation and attempted to unite to fix the problems. However, it wasn’t until the arrival of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg that any progress was made.

|

| Henry Melchior Muhlenberg by C.W. Paech, copied by J. Eichholtz image held at LACP |

Ministerium of Pennsylvania

|

| Signatures of the President and Secretary of the MOP during the formal recording of the MOP's constitution. From A5 1781-1821. |

For thirty years Lutheranism in America continued in this way. But with Lutheranism continuing to grow, and with the conclusion of the Revolutionary War as well as the creation of the United States constitution, the Pennsylvania Ministerium felt that Lutheranism could not successfully go on like this, and took inspiration from the newly-formed United States government in creating a more formal constitution. So, in 1778 the Ministerium of Pennsylvania and Adjacent States came together to do so, and the constitution was officially transcribed into the MOP’s records in 1781.

With this formal constitution now formed, American Lutheranism now had a foundation for how it would exist and, especially, how the MOP would be structured. For example, the second chapter/section formalized the duties of the president, which were basically taken from the informal actions that Henry Melchior Muhlenberg had taken on previously basically the superintendent of American Lutheranism. Even though Henry Muhlenberg was no longer actively part of the MOP at this time due to his health, he definitely had thoughts on the formalization of the MOP, which can be found within his journals (which are held within our MOP collection!), and he still had some connections with it as his son and Lutheran minister, Henry Muhlenberg Jr., was the MOP’s Secretary (the President at that time was Emmanuel Schultze). |

| Image of Emmanuel Schultze's tombstone which can be found at Christ Lutheran Cemetery in Stouchsburg, Berks County, Pennsylvania |

|

| Henry Muhlenberg Jr. by C.W. Paech, copied by J. Eichholtz image held at LACP |

Interested in learning more about Lutheranism, the history of Lutheranism in America, and the Ministerium of Pennsylvania? Check out these resources!:

Lutherans in America: A New History by Mark Granquist (available at The John E. Peterson Reference Library→ call number BX8041.G67 2015)

The Lutherans in North America edited by E. Clifford Nelson (available at The John E. Peterson Reference Library → call numberBX8041. L87)

Wiki articles: Lutheranism, Martin Luther, Ministerium of Pennsylvania, Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, and Henry Muhlenberg Jr.

For more information on Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, Henry Jr., and the rest of the Muhlenberg family, visit Historic Trappe!

Comments

Post a Comment